This report examines the discriminatory implementation of probation and parole for political prisoners in Türkiye, exposing how individuals accused on political grounds—particularly members of the Kurdish political movement and the Gülen movement—are systematically denied equal access to early release mechanisms. Through analysis of domestic laws, international standards, case studies, and interviews, it documents how Prison Administrative and Observation Boards apply arbitrary criteria such as forced declarations of remorse or “disassociation from organizations,” resulting in prolonged and unjust imprisonment. The study benchmarks Türkiye’s practices against European and UN standards, highlights violations of fundamental rights, and issues concrete recommendations to both Turkish authorities and international institutions to end systemic discrimination and ensure fair, transparent, and non-political application of probation and parole.

1. Introduction

Imprisonment is a form of criminal punishment which aims to protect social order and rehabilitate an individual who has committed an offense which is punishable by a custodial sentence. However, the execution of the punishment should be carried out in accordance with the principle of protection of human dignity. Although the primary purpose of the execution process is to punish the offender, it is not only a method of punishment, but also an opportunity for the rehabilitation and reintegration of the individual into society.

The European Convention on Human Rights[1] and the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules)[2] stipulate that prisoners should be held in humane conditions and that the execution system should be free from discrimination as well as being fair. Prisoners should have access to decent accommodation, health care, education and social activities. There should be no discrimination based on gender, ethnic origin, religious belief, political opinion or any other grounds. Furthermore, rights such as probation and parole must be implemented in accordance with the law and be free from arbitrariness.

Human dignity and fairness in the execution of imprisonment are not only a legal obligation but also a conscientious responsibility of society. These principles are crucial for the protection of the rights of individuals. Otherwise, trust in the legal system is undermined and the sense of justice is eroded. Arbitrary practices lead to human rights violations and increase social polarization. Moreover, discriminatory practices increase the risk of recidivism by preventing the reintegration of individuals into society.

In Türkiye, political prisoners face systemic discrimination solely on the basis of their beliefs or alleged actions, resulting in their exclusion from fair treatment within the execution of sentences. This practice constitutes a clear violation of the rule of law—a fundamental principle whereby all individuals, institutions, and the state itself are bound by legal norms, and arbitrary exercise of power is restrained. The rule of law exists to safeguard social harmony, eliminate arbitrariness, and uphold individual rights. In this context, it is imperative that those convicted of political offences enjoy equal access to all legal entitlements, particularly probation and parole. A just penal system must guarantee equitable and dignified treatment for every prisoner, irrespective of political affiliation.

a. Scope and Purpose of the Study

In Türkiye, probation and parole practices for political prisoners exhibit notable differences compared to those applied to other categories of offenders. Although Law No. 5275[3] contains no specific provisions distinguishing political crimes, in practice, the conditions for probation and early release in such cases are subject to stricter scrutiny. Particularly, individuals convicted of offences such as “membership of a terrorist organisation” or “crimes against state security” are subject to a more stringent enforcement regime. These prisoners often undergo additional assessments, and their applications for parole are frequently evaluated with heightened caution—reflecting systemic biases against those deemed a perceived threat to the state.

In Türkiye, prisoners’ right to parole is assessed in accordance with procedures carried out by Prison Administration and Observation Boards. These boards take into account factors such as prisoners’ behaviour in prison, their potential for integration into society and their risk of reoffending when making decisions on release. However, particularly in the case of political prisoners, the Boards do not conduct these processes fairly and base their decisions on prisoners’ political identities.

Recently, such unfair practices targeting various masses, especially Kurds and the Gülen movement[4] , have increased and even become entrenched. The recent unlawful revocation of the diploma of the mayor of Istanbul from the main opposition Republican People’s Party, followed by the arrest of the mayor and a group of politicians on corruption and terrorism charges, clearly demonstrates the seriousness of the situation. Likewise, Selçuk Kozağaçlı, a human rights defender who served as the President of ÇHD and was prominent for representing victims in political trials, was arrested on 13 November 2017 on charges of “membership in the DHKP/C terrorist organization”.[5] Irreparable victimization is being experienced. The relevant authorities turn a blind eye to all these unlawful practices, and political prisoners try to struggle with a legal system that almost does not work.

This study examines the systemic discrimination faced by political prisoners in Türkiye during penal execution, particularly regarding probation and parole mechanisms. It highlights their exclusion from equal treatment under the law and denial of a fair execution regime. The key objectives are:

- Documenting Grievances – Exposing the differential trial and sentencing procedures applied to political prisoners compared to other detainees.

- Identifying Rights Violations – Assessing breaches of fundamental rights and freedoms under international law and raising global awareness.

- Ensuring Accountability – Demanding effective investigations into violations and holding responsible parties to account.

- Pushing for Institutional Action – Urging national authorities to implement corrective measures and end discriminatory practices.

- Benchmarking Against International Standards – Evaluating Türkiye’s treatment of political prisoners against its obligations under the ICCPR, ECHR, UN Nelson Mandela Rules, and Tokyo Rules on non-custodial measures.

- Mobilising Public Awareness – Amplifying scrutiny of these violations through advocacy and evidence-based reporting.

By addressing these issues, the study seeks to challenge institutionalised bias and push for reforms aligned with Türkiye’s international human rights commitments.

In order to better understand the atmosphere in the country, the study will first briefly draw attention to the social and political changes that have shaped the current situation in Türkiye, and then it will briefly discuss the rights violations arising from the prevention of the implementation of Probation and Parole measures for convicts of terrorism offenses and other political prisoners due to subjective and unjustified evaluation reports or decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards, and the necessary solutions to minimize and eliminate these violations in accordance with the CGTİHK No. 5275.

b. Methodology

This study has been prepared with the data obtained from the following sources in order to reveal the difficulties and discrimination faced by political prisoners in the context of probation and parole:

- Domestic Laws (Acts and Statutory Instruments)

- International Legislation (Conventions and Standards)

- Reports (Official Institutions and NGOs)

- Court Decisions (National and International)

- Interviews (Prison visits, interviews with prisoners’ families and relatives, letters sent by prisoners to their families and lawyers)

- Government Statements

- The Press and Other Media

The analyses in our study are based on the data in the aforementioned sources, and the reality of the cases is addressed by including concrete examples. The figures and statistics shared reveal the extent of these victimizations. All such violations mean months and even years are stolen from the lives of prisoners and their families. It should also be known that victimisations are not limited to these numbers. Apart from the rights violations included in this report, there are many cases that are not recorded. Prisoners and their relatives, who are worried about being the target of a new legal pressure, hesitate to share the unlawful decisions against them with the media and human rights organizations. The aim of this study, which is the product of the effort to minimize the victimization, is to announce the violations of rights to the relevant authorities and to offer solutions to take the necessary measures.

2. Political Prisoners and Arbitrary Convictions

a. What is a Political Prisoner?

A political prisoner is someone who is imprisoned for his political opinions, ideology, activities or belief. He is often imprisoned for criticizing government policies, expressing dissenting views or exercising their democratic rights. For a political prisoner, the offense is not breaking the law but standing up to authority or advocating ideas that offend authority. The charges in such cases are usually crimes against state security. From an international perspective, the ECtHR assesses whether a person is a political prisoner on the basis of the fairness of the proceedings and the legitimacy of the grounds for detention.

There are Political prisoners in many countries around the world. Some are journalists, some are academics, some are just ordinary citizens. What they have in common is that they have been deprived of their freedom for expressing their opinions. Their imprisonment sometimes aims only to silence the voices of different opinions and sometimes to create a climate of fear in society.

b. The Political Prisoner Controversy in Türkiye

The political prisoner debate has been going on for many years. Political authorities have targeted a different group in each period and periodically changing mechanisms of oppression have always kept this agenda hot. This concept, which has existed for a long time, manifested itself in the recent past with the 1960 coup d’état, continued with the 1980 coup d’état, and became a frequently discussed issue with the Kurdish problem in the 1990s.

Although the European Union harmonisation process in the early 2000s led to the release of some political prisoners, since the mid-2010s, especially with the Bribery and Corruption Operations against the government (2013) and the July 15 coup attempt (2016), which the AKP government blamed on the Gülen movement, hundreds of operations have been carried out and thousands of people have been detained and arrested on political charges.

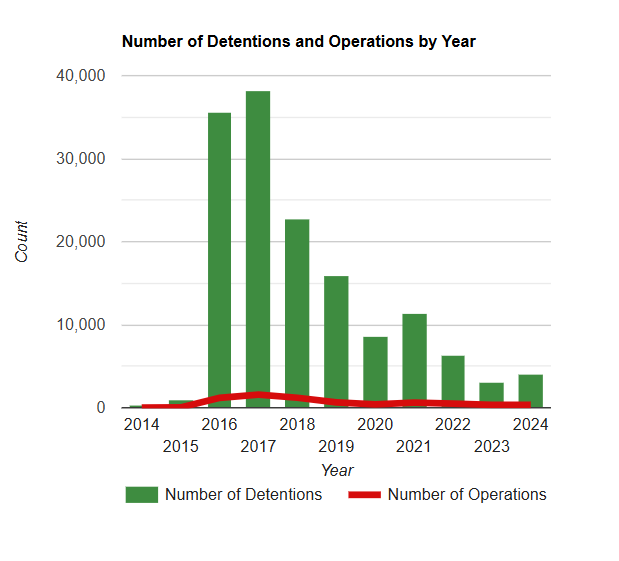

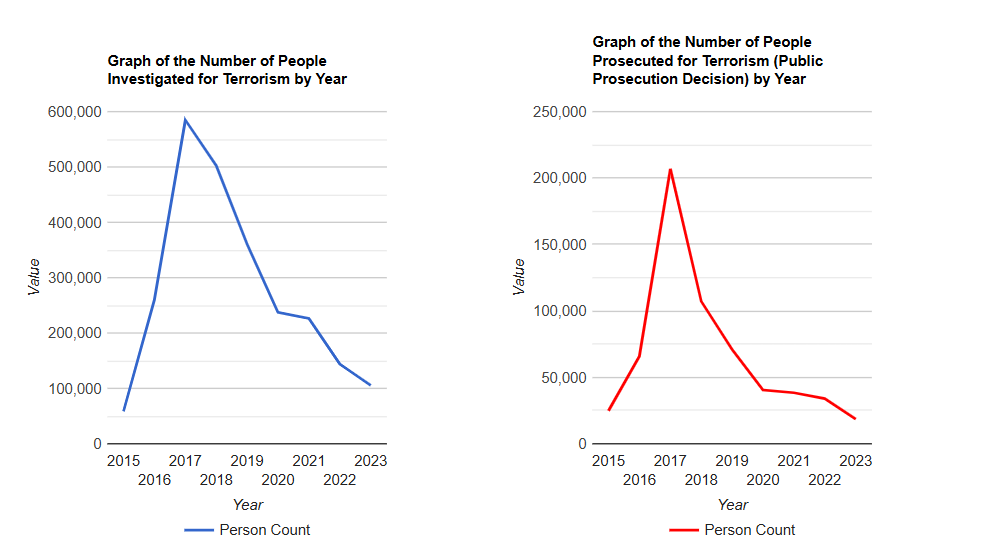

Political repression and arbitrary detentions are now a serious problem in Türkiye. The number of people detained, prosecuted and imprisoned for their political views, criticism or opposition identities exceeds hundreds of thousands.[6] This systematic campaign has led to people being unfairly labelled as terrorists or criminals and their freedoms being restricted for political reasons. The graph below shows the number of people under investigation for terrorism offenses between 2015 and 2022.

Political repression and arbitrary detentions are now a serious problem in Türkiye. The number of people detained, prosecuted and imprisoned for their political views, criticism or opposition identities exceeds hundreds of thousands.[6] This systematic campaign has led to people being unfairly labelled as terrorists or criminals and their freedoms being restricted for political reasons. The graph below shows the number of people under investigation for terrorism offenses between 2015 and 2022.

After the July 15 coup attempt, unlawful and discriminatory state practices became state policy in Türkiye, manifesting itself in various ways in society and state institutions. In many judgments of the ECtHR, it has been established that especially political investigations and terrorism trials are carried out with a trial method that is far from the Constitution and universal principles of law. The most prominent of these judgments is Yalçınkaya v. Türkiye.[7] The judgment found violations of the rights of the applicant, who was charged with membership of a terrorist organization, severely criticized the arbitrariness in terrorism trials and called on Türkiye to solve the ongoing systemic problem as soon as possible.

After the July 15 coup attempt, unlawful and discriminatory state practices became state policy in Türkiye, manifesting itself in various ways in society and state institutions. In many judgments of the ECtHR, it has been established that especially political investigations and terrorism trials are carried out with a trial method that is far from the Constitution and universal principles of law. The most prominent of these judgments is Yalçınkaya v. Türkiye.[7] The judgment found violations of the rights of the applicant, who was charged with membership of a terrorist organization, severely criticized the arbitrariness in terrorism trials and called on Türkiye to solve the ongoing systemic problem as soon as possible.

A review of the relevant data and statistics shows how widespread such arrests and detentions have been. Between 2015 and 2021, prosecutors signed 2,217,572 decisions in different terrorism investigations. Ministry of Justice data shows that in the same period, 561,388 people were prosecuted for terrorism offenses and 374,056 people were convicted by the courts on terrorism charges.[8] As of 2025, according to updated data, a total of 2,478,734 people has been investigated, 616,116 people have been prosecuted and 379,091 people have been convicted. Of those convicted, 3,763 people are under the age of 18.[9]

Many politicians, journalists and educators are currently imprisoned for their ideas, ideologies or social groups they belong to.[10] Kurdish politicians, including former HDP Co-Chair Selahattin Demirtaş, are either serving sentences or being held in pre-trial detention.[11] In the post-2016 period, the vast majority of political prisoners in Türkiye, particularly those subjected to arbitrary detention and imprisonment, are associated with the Gülen movement.[12] The AKP government’s widespread campaign of arrests and detentions against the Gülen movement has resulted in a larger percentage of people being detained and convicted on terrorism charges than for other types of offenses.

United Nations human rights experts have reported on the systematic repression of the Gülen Movement in Türkiye. UN Special Procedures have publicly expressed concern about Türkiye’s use of anti-terrorism laws to target the Gülen Movement, noting mass arrests, transnational abductions, legal purges, torture and unfair trials.

- 10 March 2025: At a recent side event at the UN Human Rights Council (HRC 58), Ben Saul, UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms while countering terrorism, cited the Gülen Movement as an example of unfair trials, coerced confessions, torture, political interference in courts, excessive detention and inhumane prison conditions, and a case of judicial misconduct against Gülen-linked individuals under Türkiye’s counter-terrorism framework.[13]

- 21 January 2025: In their communication AL TUR 7/2024, the UN Special Rapporteurs reiterated their previous concern (AL TUR 5/2024) that Türkiye’s designation of the Gülen Movement as a terrorist organization lacked legal basis and did not meet international procedural standards.[14]

- 29 November 2024: The UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (Opinion No. 33/2024, as well as 28 other opinions) expressed serious concern at the alarming increase in arbitrary detentions of the Gülen movement in Türkiye. The report warned that systematic detention and severe deprivation of liberty could constitute crimes against humanity.

- 29 October 2024: In a statement titled “Weaponizing Counterterrorism and National Security to Imprison Human Rights Defenders in the Middle East and North Africa”, Ben Saul documented how Türkiye has used terrorism charges to detain political opponents and human rights defenders beyond legal limits and deny them access to lawyers. The statement also noted that thousands of people face legal purges related to the Gülen Movement. [15]

- 7 October 2024: Another communication, AL TUR 5/2024, exposed Türkiye’s systematic crackdown on individuals affiliated with the Gülen movement, detailing mass detentions, cross-border abductions, abuse of terrorist “grey lists” and monitoring violations. The UN emphasized that Türkiye’s Anti-Terror Law No. 3713 and Penal Code are overly broad and allow for abuse against dissidents, journalists and members of civil society. Türkiye’s designation of the Gülen Movement as a terrorist organization lacks legal justification and does not meet international judicial standards.[16]

This official correspondence proves that the United Nations is fully aware of the ongoing persecution of the Gülen Movement and officially recognises it. This is a clear message to Türkiye that its abuse of anti-terrorism laws violates international human rights standards and will not go unnoticed.

In the Views adopted by the United Nations General Assembly Working Group on Arbitrary Detention at its 100th session, August 26-30, 2024, “the Working Group noted a significant increase in the number of cases brought before it concerning arbitrary detention in Türkiye over the past seven years.“

(Article 87), “The trials of Mr. Öztürk and other defendants were conducted in violation of the principles of a fair trial. Detailed defenses to the charges against the defendants were not taken into account” (Articles 33-35), referring to systematic arbitrary detention practices and the lack of fair trials. At its ninety-sixth session, from March 27 to April 5, 2023, the Human Rights Council Working Group on Arbitrary Detention considered Opinion 3/2023 on Ali Ünal in Türkiye. The Working Group has observed a significant increase in cases of arbitrary detention in Türkiye over the past six years. The Working Group expressed deep concern at the recurring pattern of these cases and recalled that, in certain circumstances, widespread or systematic imprisonment or severe deprivation of liberty, contrary to fundamental principles of international law, may constitute crimes against humanity.[17]

On 29 October 2024, the United Nations Special Rapporteur Ben Saul reported that the definition of terrorism in the Anti-Terrorism Law contains broad and vague terms, such as “pressure, force, violence, threats or intimidation aimed at changing the characteristics of the Republic“, and that it could include legitimate democratic activities such as peaceful protest, trade union action, demand for change through public pressure; that there have been widespread legal purges, particularly of individuals allegedly linked to the Gülen movement; that the independence of the judiciary in Türkiye has been seriously undermined, with lawyers under pressure and even imprisoned for defending their clients; and that there is international pressure on exiled dissidents, including trials in absentia, travel bans and asset freezes. Ben Saul’s statements point to a serious and systematic problem in Türkiye where anti-terrorism laws are used to suppress legitimate dissent and silence human rights defenders. The Rapporteur emphasizes that these practices not only violate the rights of individuals but also undermine the global human rights order.[18]

c. The use of membership of a terrorist organization and crimes against constitutional order as a tool to target dissent in Türkiye

Political, legal and social structures in Türkiye have changed significantly in the last decade. This is directly related to the AKP government’s targeting of the Gülen Movement through political pressure, especially after the July 15, 2016 coup attempt. The government suddenly declared hundreds of thousands of people in this social group as terrorists, triggering years of trials.

i. Post-Coup State of Emergency Restrictions

In the aftermath of the coup attempt, hundreds of thousands of people have been detained and arrested in Türkiye. The government has rapidly and unpredictably imposed restrictions on fundamental rights and freedoms in a manner that disregards the fundamental principles of law, citing the fight against terrorism and the post-coup “state of emergency”. During the state of emergency, the right to access to justice has been restricted along with the legal remedies available to individuals. Those arrested on the grounds of membership of a terrorist organization were often kept in prison for years pending trial and their submissions and appeals were not taken into account. The execution regime has been toughened for offenses that threaten the constitutional order and individual freedoms have been significantly restricted. Charges were broadly defined and individuals were targeted solely for their political opinions, journalistic activities or social criticism, without clear and concrete evidence of their guilt.

ii. Presidential Government System and Control of the Judiciary: An Invincible and Unquestionable Administration

The administration has become more oppressive and authoritarian with the “presidential government system”, which was adopted by the April 16, 2017, referendum and put into practice on July 9, 2018.[19] This is because the Presidential Government System has directly delegated executive power to the President. In particular, the appointment of the majority of the members of the Council of Judges and Prosecutors (HSK) directly by the executive has cast a shadow over the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, and it has become impossible to seek justice in political cases due to the pro-government stance of the judiciary. Judges who criticised or opposed the government’s policies were punished and even dismissed. The judiciary has gradually moved away from the rule of law and turned into an instrument of the government. This eroded accountability and caused the administration to be able to avoid above scrutiny and made its actions unquestionable.

The government has used law enforcement and judicial authorities as tools to crack down on members of the Gülen movement, which they have declared an “armed terrorist organization”, and all state resources have been spent for this purpose. A “witch hunt” was launched without discriminating between women, children, the sick and the elderly, and prisons were overcrowded with mass detentions and unjust arrests.[20] The government has brought all civil servants and institutions under its control, including the judiciary, and hundreds of thousands of people have been investigated and prosecuted for carrying out unlawful orders by state employees at all levels for fear of being dismissed from their jobs.

iii. Restriction of Press Freedom

In recent years, media freedom and diversity have been severely restricted in Türkiye, and a monolithic pro-government media structure has come to dominate. This process has developed in parallel with the government’s repressive policies and tight control over the media. Restrictions on media freedom have become an obstacle to social criticism and the free expression of different views and opinions.[21]

Restrictions on access to the internet and access barriers put Türkiye in the back rank among other countries in the world. According to the October 2023 Freedom on the Internet report by the US-based think tank Freedom House, Türkiye ranks 55th out of 70 countries in the list of countries where the internet is not free in 2023. The report also emphasized the Turkish government’s use of artificial intelligence to manipulate public opinion before the elections.[22] According to 2025 data, Türkiye ranked 159th out of 180 countries in the World Press Freedom Index.

The government’s pressure on the media has not only been limited to content control but has also deepened with the arrest and punishment of journalists. In many cases, journalists who criticized the government’s practices were arrested or convicted on broad and vague charges such as “spreading terrorist propaganda” or “bringing the state into disrepute“. This has led journalists to be more cautious in their reporting, in particular avoiding stories critical of the government. As a result, the media has ceased to be an independent monitoring mechanism and has become a tool to defend the interests of the government and manipulate public opinion. Dunja Mijatovic, former Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, in her report recording her observations on human rights, freedom of expression and independence of the judiciary in Türkiye, pointed out that freedom of expression and freedom of the press have declined at an alarming level in Türkiye and that 90% of the media is under government control, which hinders democratic debate.[23]

As an indication of the current state of the press, Freedom House, in its 2025 report, assessed Türkiye as “Not Free” in terms of press freedom and stated that press freedom is severely restricted in the country. [24]

iv. Climate of Fear and Threat: Mass Manipulation

In recent years, journalists, academics, activists and ordinary citizens who criticize the government have found themselves in danger of arrest or dismissal from their jobs solely for making statements within the scope of freedom of expression.[25]

This climate of repression has seriously affected the social fabric of society, undermining social solidarity and political freedoms. Fearing for their jobs, their families or their personal safety, people remain silent and are unable to go beyond the limits set by the government. This has led to the desensitization of large parts of society to the system and even to a culture of fear.

The suppression of opposition and social freedoms, the intimidation of the public, and the control of the media and the judiciary have led the government to rely on the will of a single person or group rather than the will of the people.[26] As a reflection of all these, prisoners labelled as political criminals have not received a fair trial and have been subjected to discriminatory practices in prison.

3. Probation and Parole

Parole is a practice that enables the convict, who has spent a part of the law with good behaviour and in full compliance with the rules, to be released by a decision to be taken by the relevant authority and to facilitate the transition to life without completing the entire period of conviction. Probation, on the other hand, allows the convict to be released from prison before the parole period. These execution practices have recently been on the agenda in Türkiye due to discriminatory practices against political prisoners. [27]

a. The Decision-Making Body Behind Arbitrary Imprisonment: Prison Administrative and Observation Boards

Prison Administrative and Observation Boards are an important part of the penal system. They manage the rehabilitation process of convicted prisoners, assess their disciplinary situation in prison and take important decisions such as probation or parole. The functioning of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards is determined by the Law on the Execution of Sentences and other legal regulations, and their decisions must be carried out in accordance with the law. Failure to do so may lead to irreparable violations of rights.

i. Structure, Duties and Authorities of the Board

The Prison Administration and Observation Board meets under the chairmanship of the prison director. The members are selected from different areas of expertise in the prison, such as psychologists, social workers and educators. In addition, lawyers and health personnel may also sit on the board.

One of the most important elements in determining the legal status of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards is the duties they undertake and the powers they have. Law No. 5275 on the Execution of Sentences defines the duties of these boards as follows

- Rehabilitation and Good Conduct Assessment: The board evaluates the rehabilitation processes of convicts. It evaluates the attitudes and behaviours of the convicts in prison and decides whether they are in good behaviour or not. This decision is the basis for making decisions in favor of the convict, such as parole.

- Probation and Parole: The Board decides on the Probation and Parole rights of convicts. These decisions are based on the prisoners’ behaviour in prison, their risk of recidivism and their rehabilitation process.

- Disciplinary Penalties and Violations: The Board also acts as an authority that evaluates disciplinary penalties of convicts. They can impose penalties on convicts who do not comply with the disciplinary rules in prison.

However, it is observed that the committees take different approaches in their evaluations and administrative processes depending on the nature of the crimes committed by the inmates. The distinction between persons convicted of criminal offenses and persons convicted of terrorist offenses directly affects the structure and functioning of prison administration.

ii. Structure and Functioning of the Board in terms of Criminal Prisoners

For inmates convicted of criminal offenses, the Administrative and Observation Board has the standard structure described above. The Board’s decisions on these inmates are based mainly on individual assessments, internal cohesion and the level of compliance with disciplinary rules. The Board’s assessments are based on:

- Disciplinary sanctions and rewards

- Psychological state

- Training and improvement activities attended

- The process of acquiring a profession

- Internal relations

In this respect, judicial prisoners are assessed on the basis of their potential for individual recovery and decisions are based on more objective criteria.

iii. Structure and Functioning of the Board for Terrorism Prisoners

Although there is no direct legal provision on the structural differences in the Administrative and Observation Board for persons convicted of terrorism offenses, there are serious differences in practice and interpretation of the legislation. These differences can be categorized under the following headings:

- Public Security: In high-security prisons housing terrorism offenders, the board’s decisions are based not only on individual behaviour but also on abstract criteria such as ongoing loyalty to a criminal organisation and ideological dissolution.

- Difficulties in Assessing Good Behaviour: When assessing “good behaviour” for terrorism prisoners, not only the absence of disciplinary punishment is not considered sufficient, but also factors such as whether they have shown remorse, whether they have made statements and behaviours indicating that they have left the organization.

- Monitoring and Reporting Processes: Reports on terrorism offenders are kept more frequently, and pre-board evaluation processes are more detailed and multifaceted. Close coordination is ensured between psychologists, social workers and intelligence units.

- The Effect of Internal Dynamics on the Board’s Decision Making Process: Security units of the institution and intelligence reports have more weight in the evaluations of persons convicted of terrorism offenses. This causes the decisions of the board to be shaped more cautiously and against possible security risks.

- Prosecutor Presiding the Board: When the Administrative and Observation Board evaluates those convicted of terrorism offenses, the chief public prosecutor or a public prosecutor to be designated by the chief public prosecutor chairs the Administrative and Observation Board in evaluations regarding the allocation to open penal institutions, the execution of the sentence by applying probation measures and parole. In addition, a member of the Observation Board determined by the chief public prosecutor and an expert determined by the provincial or district directorates of the Ministry of Family, Labor and Social Services and the Ministry of Health shall participate in the administrative and observation board.[28] The fact that the Chief Public Prosecutor, who is the prosecuting authority in the trials, or a prosecutor of his choice, chairs the board is quite unfair for the convicted person who has already been found guilty and convicted. In addition, it is also observed that the prosecutor can appoint members to the board. It is certain that the convict will not be subject to an objective evaluation under these circumstances.

The main difference between judicial and terrorist prisoners is not only in the way the Administrative and Observation Boards operate, but also in the decision-making mechanism. While judicial prisoners can be evaluated with more objective criteria, for those arbitrarily convicted of terrorism offenses with political motivation, decisions are more security-oriented, based on the expectation of ideological dissolution and shaped according to intelligence information. This situation leads to the perception of inequality and discussions, especially in the parole and execution regime.

iv. The Nature of Board Decisions

Prison Administrative and Observation Boards, through their decisions, determine both the prison administration and the way in which prisoners are sentenced. The decisions of the Board must be implemented based on regulations and the legal framework. The decisions taken by the Prison Administration and Observation Boards are binding and affect the punishment and rehabilitation processes of convicts in penal institutions.

However, the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards are under judicial supervision and some decisions can be directly appealed to the judicial authorities. For example:

- Decisions such as probation or parole may be taken by the Prison Administration and Observation Board but are not valid unless approved by the Correctional Judge.

- Disciplinary penalties imposed by the Prison Administration and Supervision Board can also be appealed by the convicted person to the Penal Enforcement Judge, who will review the lawfulness of the decision.

In this context, the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Board are legally binding and are subject to review by the judiciary in case of an unlawful decision.

Another important issue is whether the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Board are subject to judicial review. While the law recognizes the right of defence of convicts, it also establishes that the decisions of the board are subject to judicial review. This means, in particular, that decisions related to the rehabilitation and sentencing processes of convicts are subject to judicial review.

- Judicial review of the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Board is usually carried out by a “Judge of Execution”. The Judge of Criminal Execution checks the legality of the decisions taken by the board and ensures that a fair process is in place to prevent violations of prisoners’ rights.

- Decisions, such as parole, cannot be implemented unless approved by the Correctional Judge. Therefore, a decision of the Prison Administration and Observation Board does not have direct legal consequences and is subject to judicial review.

Although it is accepted in theory that the functioning of the board and its decisions are subject to certain rules, this is not the case in practice. Both the changing approach to the type of offense and the ineffectiveness of the appeal authorities render the oversight mechanisms dysfunctional and lead to unlawful decisions in operation.

v. Revocation and Amendment of Board Decisions

The legal nature of the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Board is based on the principle of compliance with the law. The Prison Administration and Observation Board must take fair and impartial decisions that do not violate the rights of prisoners. If the decisions are not made in a legal and fair manner, the decision may be annulled by the Judge of Execution of Sentences and replaced by a decision in accordance with the law. For example, if the Prison Administration and Observation Board has made a decision on parole, but this decision contains a deficiency in the legal framework or a violation of the law, the Execution Judge may annul this decision.

Pursuant to Article 5 of the Law on the Judgeship of Execution, a complaint may be filed with the Judgeship of Execution within 15 days from the date of learning of the actions taken against convicts and detainees in penal execution institutions and detention centers or the activities related to them on the grounds that they are contrary to the provisions of laws, by-laws and regulations and circulars, and within 30 days from the date of execution.

As stated in Article 6 of the Law on Judgeship of Execution, the judge of execution, at the end of the examination, if he/she does not find the complaint justified, decides to reject it; if he/she finds it justified, he/she decides to cancel the action taken or to suspend or postpone the activity.

The decision of the Criminal Execution Judge can also be appealed to a higher court. If the Execution Judge also decides without finding a violation of the law, the convict can challenge this decision again through judicial review. An appeal against the decisions of the Execution Judge can be filed to the Assize Court within one week of the notification.

An individual application can be filed to the Constitutional Court against the decision of the High Criminal Court upon objection within 1 month from the date of notification. The negative decision of this court can be appealed to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) within 4 months.

b. Periods and Conditions for Probation and Parole in Turkish Law

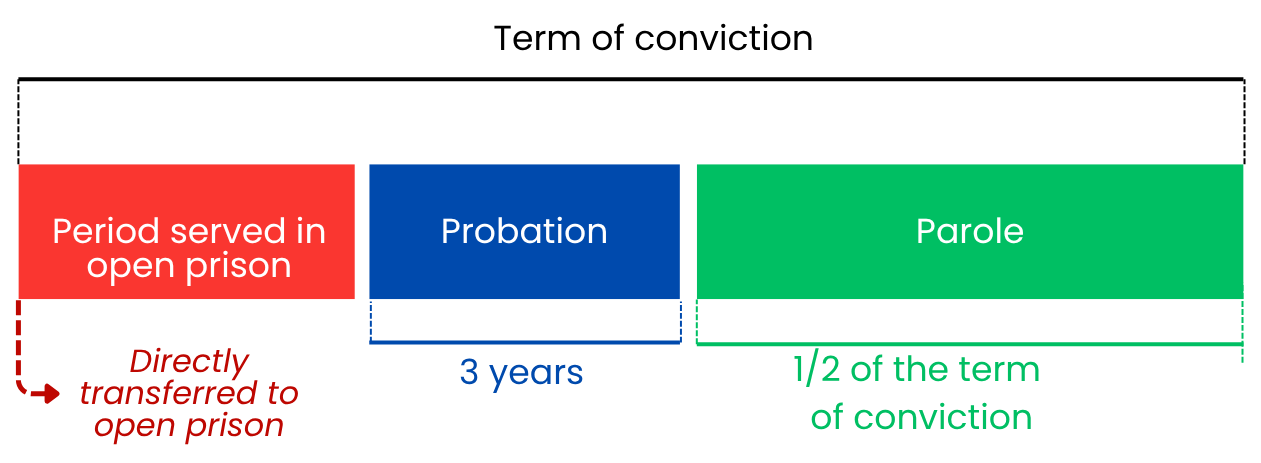

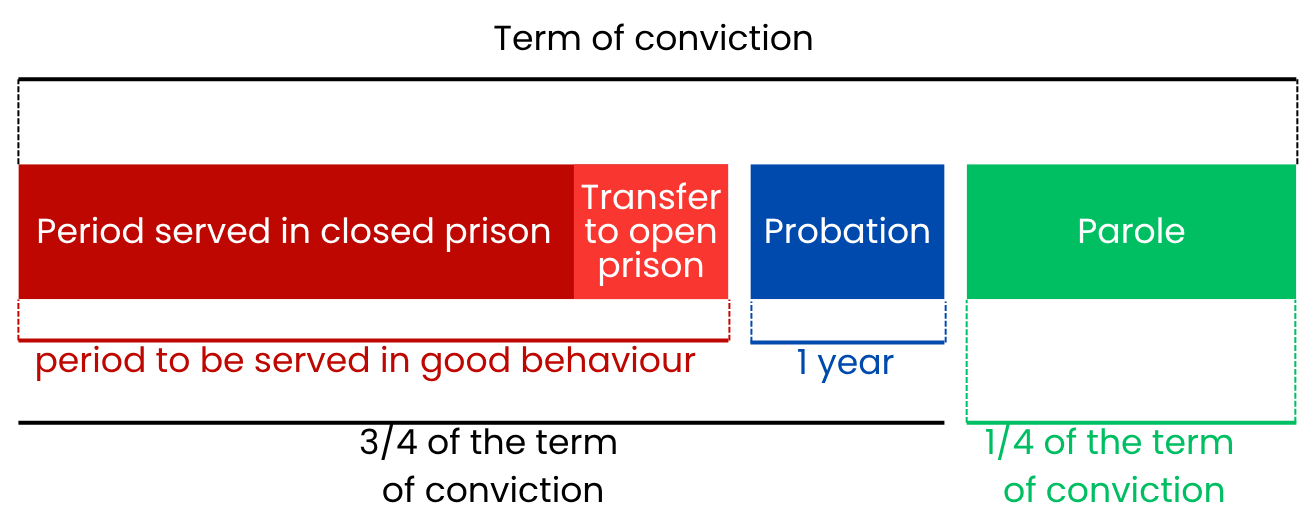

In the Execution Law, parole periods are determined according to the types of crimes. Accordingly, persons convicted of judicial crimes can exercise their right to parole when they complete 1/2 of their entire sentence, and persons convicted of catalogue crimes can exercise their right to parole when they complete 2/3 of their sentence. A higher rate has been set for terrorism, narco and sexual crimes, and it has been regulated that convicted of these crimes can benefit from parole if they complete 3/4 of their sentences.

According to Articles 14, 89, 105/A of the Law No. 5275 on the Execution of Criminal and Security Measures and Article 6/ç of the Regulation on Separation to Open Penal Execution Institutions, the following conditions are required for terrorist convicts to be granted probation:

- 1 year or less to be left for parole.

- To have the necessary conditions for leaving to the Open Penal Execution Institution.

- The Prison Administration and Observation Board decides that he/she is in “good behaviour”.

- It is determined by the administration and observation board that he/she has left the organization to which he/she belongs.

- The convict requests the application of probation.

- Decision of the execution judge.

The departure of convicts from Closed Penal Execution Institution to Open Penal Execution Institution is decided as a result of good behaviour evaluation. Those convicted of terrorism offenses may be transferred from Closed Penal Institution to Open Penal Institution after the decisions of the Administrative and Observation Board are approved by the execution judge.

The Prison Administration and Observation Board, at least once every 6 months, decides whether the convict is in good behaviour by taking into account the improvement and education-training programs, sports and social activities, culture and art programs, certificates received, reading habits, relations with other convicts and detainees, penal execution institution officials and the outside, remorse for the crime committed, compliance with the rules of the penal execution institution and the rules of work within the institution and the disciplinary penalties received, by evaluating the convict in the context of the following conditions:

- Compliance with the rules of penal execution institutions.

- Using his/her rights in good faith.

- Having fulfilled his/her obligations completely.

- Readiness to integrate into society according to the rehabilitation programs implemented.

- Low risk of reoffending and harming others.

All these criteria have been introduced in order for the board to make objective evaluations free from arbitrariness when making decisions about convicts. In addition, these evaluations and the decision to be made must be justified and based on the information and documents in the convict’s file. The Board shall evaluate the convict’s good behaviour based on the above criteria. It is possible for the convict to benefit from parole and to be separated to open prison by applying probation measures to him/her, if the board decides that he/she is in good behaviour.

c. Discriminatory Execution Practices

Political prisoners in Türkiye are labelled as terrorists and sentenced to long years in prison on baseless and trumped-up charges solely because they are dissidents. Moreover, they are also subjected to discriminatory execution practices as a secondary punishment. While ordinary criminals who are sentenced to a similar period of imprisonment usually serve even half of their sentences in closed penal institutions, Political prisoners often serve their entire prison sentences in closed prisons. To illustrate this inequality in a more understandable way:

For a prisoner convicted of extortion:

- Sentence Length: 6 years and 3 months.

- Eligibility for Parole: 3 years, 1 month and 15 days.

- Eligibility for Probation: 1 month and 15 days.

- Actual Time of Incarceration (in practice): 1 month and 15 days.

For a political prisoner:

- Term of Conviction: 6 years and 3 months.

- Eligibility for Parole: 4 years, 8 months and 10 days.

- Eligibility for Probation: 3 years, 8 months and 10 days.

- Total Prison Term (without Probation and Parole): 6 years and 3 months.

As it can be understood from the example, a political prisoner sentenced to 6 years and 3 months imprisonment can spend the whole of this period in a closed prison if his parole request is rejected. Even in cases where they benefit from parole, they can remain in a closed penal institution for about five years. In this way, political prisoners are subjected to both arbitrary detention and prolonged imprisonment. This contradicts the UN Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Nelson Mandela Rules), in particular Rule 39, which states that no prisoner shall be punished twice for the same act or offense and emphasizes the principles of justice and fair trial.[29]

i. Struggles for Release: A Different Assessment of Good Conduct for Political Prisoners

According to current data from the UYAP Information System, the number of people benefiting from probation in Türkiye is 2,098 per day, 162,806 per year and 242,242 in total.

Although at first glance, the figures suggest that the current situation is promising and that many people are being rehabilitated through this institution, this is not the case. Although the above-mentioned criteria have been determined and an attempt has been made to ensure the control of legality, when it comes to political prisoners, it is seen that the Prison Administration and Observation Boards do not carry out these processes fairly and make their decisions based on the political identities of the convicts. Especially good conduct evaluations are often different for political prisoners and other prisoners. While a behaviour that does not violate prison rules may lead to disciplinary punishment for a political prisoner, it is ignored for another prisoner.

It is also worth noting that the latest figures published by the Turkish Statistical Institute in the context of terrorism offenses are for the period 2020-2022. There is no up-to-date data sharing for the last years, and therefore there is not enough transparency regarding the trials. Therefore, there is uncertainty as to what proportion of the numbers given above regarding those benefiting from probation are related to terrorism offenders. When the board decisions regarding political prisoners are examined, it is understood that the rate of political prisoners benefiting from favourable execution practices is quite low.

In the latter case, while prisoners convicted of ordinary crimes benefit from favourable execution practices, political prisoners are often subjected to discriminatory treatment that denies them access to these practices. Some of the factors that lead to this are:

- Politically Motivated Decisions: Political ideologies and differences of opinion play a major role in the evaluations made on political prisoners. The approach of the government or prison administration, which aims to punish political prisoners, has a negative impact on probation and parole applications.

- Flexibility of the Criteria for Parole and the Extent of the Administration’s Discretion: Although parole applications are mostly based on certain criteria, when applied to political prisoners, they are flexible and arbitrary decisions are taken. Subjective evaluations made while taking into account the time spent in prison, behaviour and other conditions affect the decisions.

- Harassment and Abuse in Prison: Political prisoners are subjected to more severe pressures and bullying in prison, and psychological pressure, physical violence or social exclusion can make their rehabilitation process more difficult. Such prisoners are less likely to be eligible for probation and parole on the grounds that they have not completed their rehabilitation process.

- Pressure on Good Conduct Scoring: It is frequently observed that the government exerts direct and indirect pressure on Prison Administration and Observation Boards and prison administrations regarding the “good behaviour” score of political prisoners. As a result of these pressures, the boards, regardless of legal criteria, consider the behaviour of political prisoners as contrary to the system and do not give them points; they pave the way for rights violations through disciplinary penalties.

ii. Probation and Parole for Sick Political Prisoners in Türkiye

In Turkish law, the provisions on the release of sick prisoners are regulated by Law No. 5275 on the Execution of Sentences and Security Measures. However, the discriminatory practices against political prisoners mentioned in detail above also appear here. Although the conditions for political prisoners are met, their requests for probation and parole are rejected and unlawful practices such as not postponing the execution of sick prisoners continue.

There are hundreds of political prisoners who were first arrested and then left to die in prisons despite their health conditions being too severe to stay in prison. Especially members of the Kurdish political movement and members of the Gülen movement are kept in prison because of their identity as political prisoners, even though their health conditions are not suitable for prison conditions. Unfortunately, some prisoners have lost their lives in prison conditions without adequate medical care. Some of the political prisoners who are not benefited from their probation rights despite their deteriorating health conditions:

- Soydan Akay, a 50-year-old prisoner with prostate cancer, Hepatitis B and rheumatoid arthritis, who was entitled to parole on August 11, 2023, and yet his request for parole was rejected 3 times;[30]

- Ünal Eneş, who had a stent inserted in his heart while in prison, who also suffers from blood pressure, diabetes and eczema, whom even the guards addressed as “cotton grandpa”, but whose probation was postponed for 3 months by not even appearing before the board;[31]

- Mustafa Başer, a dismissed judge who suffers from cancer, who was not released despite his right to probation, who was made to serve his sentence in solitary confinement, whose cancer relapsed for the third time and who was almost left to die;[32]

- Halil Karakoç, 84 years old, seriously ill and in need of care, who suffered a heart attack in prison, whose request for probation and parole was rejected without justification despite his good behaviour during the execution process;[33]

- Lawyer Ali Odabaşı who underwent 4 surgeries in prison, was handcuffed to a bed whilst in hospital, whose request for supervised release was first answered as being in good behaviour and then as not being in good behaviour despite having no disciplinary penalty;[34]

- İsmet Özçelik who was kidnapped by MIT from Malaysia and brought to Türkiye, who suffers from heart disease and diabetes, who was sentenced to disciplinary punishment for making rosary beads from olive pits, whose request for supervised release was arbitrarily rejected on the grounds of this unlawful punishment;[35]

- Adil Somalı, whose execution of his sentence was completed and whose request for Probation and Parole could not be evaluated due to the failure of the board to convene, and whose prison term was automatically extended, and who, upon learning of this, had a seizure, fell into a coma and died.[36]

iii. Written Question Proposals: Cries for Justice in Parliament

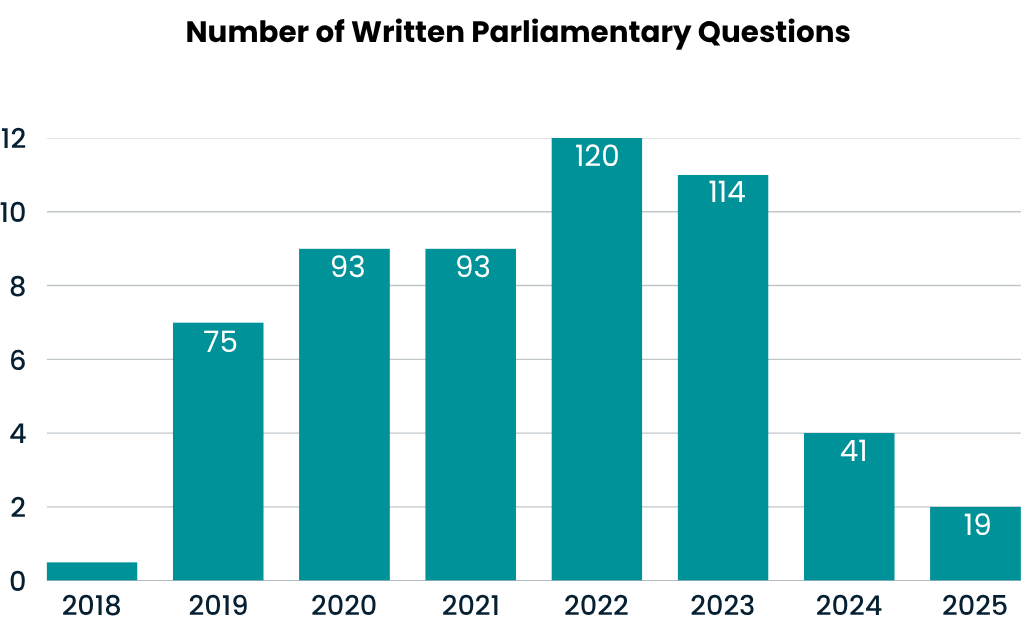

Since 2018, more than 500 written parliamentary questions on the subject have been submitted by Members of Parliament (MPs) through oversight mechanisms of the legislature.

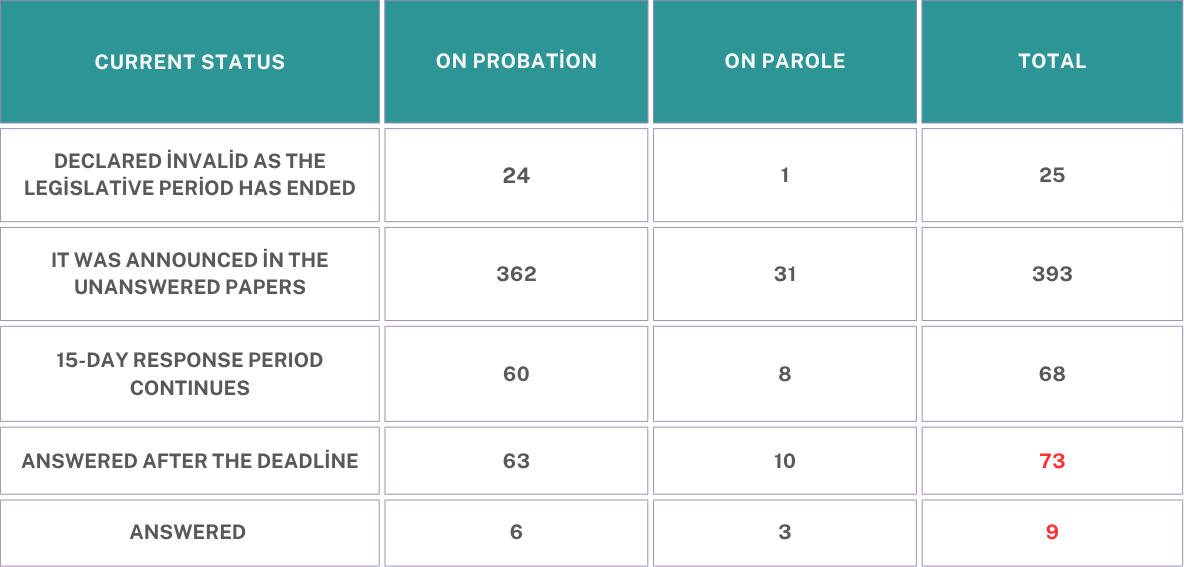

Between 2018 and 2025, a total of 515 written questions on probation and 53 on parole were submitted.[37] These questions asked the Minister of Justice to respond to allegations of violations of probation and parole rights. Only 9 of these parliamentary questions were answered within the legal deadline of 15 days, while 73 were answered after the legal deadline. Unfortunately, 25 parliamentary questions are still pending response, and 461 parliamentary questions were simply not answered.

Some of the parliamentary questions that were answered after the deadline were responded to uniformly. They do not contain concrete answers to the allegations. In the majority of cases, the response was simply that “Probation practices are carried out in accordance with the provisions of the legislation”. Moreover, it is important to emphasise that the Ministry of Justice has been conspicuously silent on this issue for the last three years, further deepening concerns about the lack of transparency and accountability in the implementation of probation and parole rights.

A closer examination of the allegations of violations reveals specific regions and prisons where these concerns are particularly pronounced. Afyonkarahisar tops the list with 36 cases, followed by Sincan with 35 cases. In addition, Izmir, Antalya, Tekirdağ, Tekirdağ, Manisa, Tokat, Yozgat, Niğde and Samsun exhibit notable concentrations, with case reports ranging from 11 to 22 in each region or facility.

iv. Current Problems in the Execution of Sentences of Political Prisoners

In a fair regime of execution, convicts who meet the conditions listed in the law should be decided to be allocated to an open penal execution institution without any further conditions in accordance with the “principle of equality”, which is one of the most fundamental principles protected by the Constitution and other international authorities. It is a requirement of being a state of law that the convict should benefit from these rights. However, an examination of the handling of probation and parole requests of political prisoners reveals some recurring patterns in violation of the principle of equality. Below, these discriminatory practices that have become established practices are mentioned, the sources of the problems are identified, and concrete cases are given.

Inadequacy of Legislation

The law lists subjective criteria such as rehabilitation, return from crime and behaviour in prison as conditions for benefiting from probation and parole. However, it is debatable how objectively these criteria are evaluated by the Prison Administration and Observation Boards, and it has been demonstrated by the above-mentioned examples that these criteria are not evaluated fairly, especially for political prisoners. Due to criteria that are not detailed and clearly outlined in laws and regulations, convicts are subjected to arbitrary discrimination based on their political identity.

Problems Arising from the Decisions on the Determination of the Convict’s Separation from the Organization to which he/she belonged (Verification of Sincerity)

In order for a prisoner who has been tried for terrorist crimes and organized crimes to benefit from probation and parole, it is necessary to “determine that he/she has left the organization”. Although there are some criteria in the regulation on how to determine whether the prisoner has disassociated from the organization or not, there are inconsistencies in practice.[38] Inconsistent decisions taken by the Prison Administration and Observation Boards lead to contradictions in practice. Many prisons have established their own arbitrary evaluation criteria and reject many prisoners’ requests for probation and parole on abstract grounds.[39]

While whether a person is a member of an organization or not can only be determined through a trial, the fact that an administrative board determines whether the person is or is not affiliated with the organization constitutes a contradiction in legal terms.

In addition to all that, the requirement for the convict to declare that he/she no longer has any ties to the organization also poses a problem. In all stages of the trial (there are many ECtHR judgments that support this claim), the prisoner, who defends that he is not a member of any organization and denies all the accusations, declaring that he is “no longer affiliated with the organization” in order to use his rights to leave the Open Prison Execution Institution and to benefit from probation, would mean retrospectively admitting the accusation and accepting the accusation that he denied from the beginning, but no one can be forced to make a statement against himself. This situation clearly contradicts the provision of Article 38, paragraph 5 of the Constitution, which reads, “No one shall be compelled to make a statement incriminating himself or his relatives specified in the law or to show evidence in this way.”[40]

As an example of this issue, Hüseyin Yıldırım, a lawyer registered with the Bitlis Bar Association, stated that his client was subjected to arbitrary practices in the evaluation of his client’s benefit from supervised release and shared the following:

Another issue that should be mentioned is that the Administrative and Observation Board should make the determination of good behaviour and whether the convicts who are entitled to be separated to open penal execution institutions or who will soon be entitled to this right should make the determination of whether they have left the organization ex officio, not upon request. Because Article 10 of the Regulation on Separation to Open Penal Execution Institutions/7; “Even if the convicts do not request, if there is no risk in their accommodation in the open institution and if they meet the conditions specified in this Regulation, they are sent to the open institution ex officio by the chief public prosecutor’s office upon the decision of the administration and observation board.“, it is regulated that if the convict meets the conditions for separation to an open penal execution institution, let alone making a written or verbal declaration that the convict has left the organization or has no ties with the organization, an ex- officio action will be taken without the need for the convict to make a request in this direction.

In summary, the fact that a convict does not make a statement that he/she has left the organization does not indicate that he/she has ties with the organization. Because many convicts argue that they have no ties with the organization from the beginning and they see an acceptance to the contrary as accepting a crime they did not commit, this will of the convict should be respected in the execution of the sentence and the convict’s right to transfer to an open penal institution should not be taken away from the convict just for this reason. What is important is to make concrete determinations as to whether the convict has ties with any organization in terms of his/her attitudes and behaviours reflected to the outside world. It should be accepted as a presumption that the convict has severed ties with the organization, the burden of proof regarding claims to the contrary should belong to the board and the legal regulation should be corrected in this way.

Problems arising from the condition of the convict’s remorse

Article 89 of the Execution Law No. 5275 states that “…in the evaluation to be made, the improvement and education-training programs, sports and social activities, culture and art programs, certificates received, reading habits, relations with other convicts and detainees, penal execution institution officials and the outside, remorse for the crime committed, compliance with the rules of the penal execution institution and the rules of work within the institution and disciplinary penalties received are taken into consideration.”

Although it is an administrative board, the Administrative and Observation Board acts like a court when evaluating in the context of the mentioned criteria.[41] When deciding whether the inmate is in good behaviour despite having a finalized criminal conviction, it asks whether he/she regrets the crime he/she committed.[42] “Remorse” is regulated as a reduction that the defendant may show during the investigation or prosecution phase, which may directly affect the verdict. On the other hand, the evaluation of the remorse of a convict, whose trial has been concluded and whose execution has come to an end, by a board that does not have the title of judge or court, and accordingly deciding whether he is in good behaviour or not, constitutes a violation of the “prohibition of double evaluation”, which is one of the basic principles of criminal law. In its report titled “Parole and De facto Criminal Courts in Türkiye”, the President of Magistrats Européens pour la Démocratie et les Libertés (President of Magistrats Européens pour la Démocratie et les Libertés-MEDEL) made similar observations and drew attention to the fact that the Probation and Parole rights of terrorism offenders, especially after 2020, were blocked by unjustified decisions of administrative and observation boards acting as de facto criminal courts.[43]

Another problematic issue under this heading is the expression of remorse by prisoners who do not accept the charge. A convict who says that the trial was not conducted fairly and that he is not guilty cannot be expected to show remorse. Moreover, for a person convicted of being a member of a terrorist organization, this means expecting him to accept the accusation of membership of the organization, which he rejected during the trial, during the probation assessment, then to express his regret for this, and finally to make sincere statements that he is no longer affiliated with the organization. There are many examples of this problem.[44] Political prisoners who spent their probation and parole period in good behaviour and who did not have any disciplinary penalties were found to be not in good behaviour due to their “lack of remorse” and it was decided that they could not benefit from probation.[45]

Unjustified Decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards

When deciding on the good behaviour of convicts, the Board has to justify its opinion. It is important that the decision is concrete and auditable in order to prevent the convict from being deprived of his/her rights. However, in practice, there is not enough conviction that the convict has left the organization to which he/she is affiliated[46], there is no written statement showing that the convict has ceased to be affiliated with the organization[47], the convict is asked to bring a religious book called Risale-i Nur from the prison library[48], the convict’s statement that he/she has left the organization to which he/she belongs is not sincere[49], the convict does not accept his/her guilt and therefore is not remorseful[50], the convict is not ready to integrate into society[51], the convict does not accept to be transferred to an independent ward[52], the convict has chosen not to benefit from probation and parole provisions. On the other hand, all these arbitrary evaluation criteria of the board psychologically wears down the convicts and their relatives who spend their execution period in prison in good behaviour, obey the rules, do not receive disciplinary punishment, and expect to use their rights of Probation and Parole.[53]

An example of the arbitrariness of observation board reports is the case of teacher Özcan Solmaz. The board report observed that the teacher was “psychologically not ready to adapt to social life”.

On 29/04/2024, the President Of The Association Of European Administrative Judges (AEAI), the President Of The European Association Of Judges (EAJ), the President Of MEDEL and the President Of Judges For Judges (Rechter Voor Rechters) wrote a letter to the Minister of Justice of the Republic of Türkiye, stating that the execution of the sentences of many terrorism offenders in Türkiye[54] , including former Constitutional Court rapporteur Murat Arslan[55] , is not carried out fairly, that despite meeting the conditions stipulated in the law, their right to parole is not implemented on purely arbitrary and abstract grounds, that the requests of terror convicts are rejected without any concrete reason, that “Sincan Prison” in particular has a bad reputation in this way, that the current practices contradict the principles of impartiality and equality, that there is an urgent need for a fair implementation, and that the requests of all detainees and convicts should be evaluated objectively.[56]

Other examples of arbitrariness in observation board reports:

- In the decision prepared by the Sincan F Type F No. 2 Administration and Observation Board, it was stated that “It is assessed that the convict is not ready to integrate into society according to the rehabilitation programs implemented and has a high risk of harming the victim or others.”.[57]

- Although the Observation and Administration Board of Diyarbakır Women’s Closed Prison transferred the convict to Elazığ Open Prison on January 30 for the implementation of her right to supervised release, it sent a letter to the board of the open prison and ordered the convict to remain in prison in Elazığ for another three months.[58]

- Silivri Prison No. 9 Administration and Observation Board did not find the convict’s declaration that he had no ties with the organization “sincere” and rejected his request for probation on the grounds that there was not sufficient conviction that the ties had been severed.[59]

- Since the convict’s declaration that he had left the organization he was affiliated with was not sincere and his declaration was considered to be misleading statements to benefit from probation, he was not benefited from the provisions on parole.[60],[61]

- In a written parliamentary question no. 3326 submitted to the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye on August 15, 2023, HDP Mardin MP Beritan Güneş Altın[62] shed light on the disturbing situation of a group of Kurdish political prisoners in Sincan Women’s Closed Prison. They found themselves caught in a web of arbitrary decisions by the Administrative and Observation Boards, which resulted in their continued incarceration despite being eligible for probation or parole.

Lack of an Effective Domestic Legal Remedy against Prison Administration and Observation Board Decisions

- Problems Arising from the Complaint Procedure

The Execution Judgeship is the authority that will evaluate the convict’s request for probation in the context of the decision of the Administration and Observation Board. The convict may file a complaint within 15 days against the board’s decision that he/she is not in good behaviour.[63] Upon the complaint application, the execution judge decides on the file within one week without holding a hearing, and at the end of the examination, if the complaint is not deemed relevant, it is rejected; if it is deemed relevant, it decides to cancel the decision or the action taken, or to suspend or postpone the activity.[64] However, it is observed that the execution judges mostly support the board’s assessment of inmate complaints. Execution judges decide on the implementation of probation for inmates who are deemed to be in good behaviour by the board and reject the request for probation for inmates who are deemed to be not in good behaviour by the board. The decisions, which are justified by printed and generalized statements, do not examine whether the board has exercised its discretionary power arbitrarily.[65] Complaint to the Execution Judges, which is the first step in the domestic remedy, appears to be an ineffective and useless remedy.

- Problems Arising from the Appeal Procedure

The prisoner can appeal to the Assize Court within 7 days from the notification of the decision of the execution judge on the complaint.[66] It is observed that the judges of the Assize Court reject the appeals against the decisions of the Execution Judges to dismiss the complaint on the grounds that the decision of the Execution Judges is in accordance with the law.[67] Although a remedy against the decision of the Execution Judgeship is envisaged, the review by the Assize Courts is not on the merits but is a procedural procedure. In the last case, the appeal to the High Criminal Courts is also an ineffective remedy where the legality of the board’s decisions is not reviewed.

- Dysfunctionality of the Court of Cassation’s Reviews

As mentioned above, the decision of the Assize Court as a result of the examination made upon the application for appeal is final and no appeal or appeal can be filed against this decision. In this case, it may be possible to review the legality of the board’s decision and the decisions of the Execution Judgeship and the Assize Court regarding this decision by applying for “reversal in favor of the law”, which is one of the extraordinary legal remedies.

In practice, it is observed that the Court of Cassation’s review of the reversal in favor of the law regarding terrorism offenders is no different from the attitude of the judicial authorities in other remedies. Namely, the Court of Cassation tries to legitimize the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards with inadequate examinations and abstract justifications far from the review of legality.

The Court of Cassation, apart from deeming it necessary for the convict, who did not accept the organization accusation at the prosecution stage, to obey the rules, participate in the programs, not to receive any disciplinary punishment, and to request to be transferred to a neutral ward by declaring that he has no ties with the organization when his legal period expires; the Court of Cassation deemed the decision of the board that the convict was not in good behaviour on the grounds that he did not share any information about the organization and that there was no concrete evidence that he had left the organization when his phone calls and letters were examined.[68]

In the current situation, it is observed that even the Court of Cassation, which is the highest authority to review judicial decisions, is influenced by the dynamics of the country when the subject of review is political prisoners.

- Superficiality of the Constitutional Court’s Reviews

It has been mentioned above that the Prison Administrative and Observation Boards violate the fundamental principles of the Constitution when they make decisions as a result of their examinations of prisoners. In this context, prisoners can appeal against the board’s decision to the Execution Judge and the High Criminal Court and then to the individual application, which is the last stage of domestic remedies. Here, the applicant will request the Constitutional Court to declare that the decision taken for him/her during the execution process is not in accordance with the law, that he/she has exhausted the domestic remedies and that the decisions of the relevant authorities constitute injustice, that the fundamental principles of the Constitution such as the rule of law, equality, prohibition of discrimination, reasoned decisions, and the non-arbitrary use of discretion by the administration are not applied to him/her and lead to a violation of rights, and that the necessary examinations should be made.

In practice, it is observed that the Constitutional Court renders inadmissibility decisions on such applications without going into the merits, and that the decisions it renders are contradictory in themselves. [69]

- Conflict of Administrative and Judicial Jurisdiction

The decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Boards[70] are administrative in nature and are taken by administrative bodies with executive power. Pursuant to Article 125 of the Constitution[71], administrative actions are subject to judicial review and this review must be carried out by administrative judicial authorities. However, subjecting these decisions[72], which are administrative acts, to judicial review is contrary to the principle of separation of judicial powers. This situation leads to incompatibility in terms of legal nature.[73]

Judicial review of the Board’s decisions also leads to confusion of jurisdiction. In accordance with the rule of law, there should be clarity and certainty as to which judicial authority individuals should apply to.[74] While administrative actions are reviewed by the administrative jurisdiction as a rule, reviewing the decisions of the boards by the judicial jurisdiction harms the rule of law principle and causes uncertainty in terms of division of labour and jurisdiction between the courts.[75]

Judicial jurisdictions are mainly responsible for criminal and civil cases. The transfer of the decisions of the Prison Administration and Observation Board to the judicial jurisdiction increases the workload of the courts, prolongs the duration of the proceedings, reduces the effectiveness of the judiciary and delays justice.[76]

The penal execution system is based on a certain division of labour between administrative and judicial mechanisms. Different evaluations of the decisions of the Administrative and Observation Boards by different courts disrupt the balance of the execution regime and cause inconsistencies in practice.

As a result, the judicial review of the decisions of the Administrative and Observation Boards brings with it many problems such as incompatibility of legal qualifications, confusion of authority, problems of the rule of law and legal certainty, the workload of the judicial judiciary and difficulties of implementation in terms of execution law.[77] Therefore, subjecting these administrative decisions to administrative judicial review would be a more appropriate method in terms of legal stability and judicial efficiency.[78] A regulation in this direction in the legislation is necessary in terms of both the rule of law and the protection of the rights of prisoners.

4. International Framework and Comparative Probation and Parole Practices

International legislation includes regulations to ensure that penal execution systems respect fundamental human rights principles and guarantee prisoners’ rights to equality, non-discrimination and fair treatment. These regulations prohibit discrimination in penal execution practices and aim to provide a humane approach to prisoners. International norms based on EU and UN regulations, in particular the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), the Mandela Rules, the United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), are the main documents shaping states’ practices in prisons.

- European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR): The judgments of the ECtHR are one of the main mechanisms that come into play when prisoners’ rights are violated. Article 3 (prohibition of torture) and Article 14 (prohibition of discrimination) guarantee the rights of prisoners. Article 5, which guarantees the right to liberty and security, applies to all individuals, including political prisoners. The interpretation of this article has implications for the early release of political prisoners as it emphasizes the need for equal treatment in release mechanisms based on risk assessment and rehabilitation potential.[79]

- United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (Mandela Rules): The Mandela Rules are the basic rules adopted worldwide to improve prison conditions and ensure the dignified treatment of prisoners (Rule 1). Adopted in 2015, they provide principles that reinforce equality and non-discrimination in prisons (Rules 2-3). They therefore include Political prisoners, who should have the same opportunities for rehabilitation and early release as other prisoners. The emphasis on fairness and due process in sanctions is universally applicable and ensures that political prisoners are not unfairly excluded from early release measures.[80]

- United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR): The United Nations Covenant on Civil and Political Rights upholds that all individuals have equal rights and that the principle of non-discrimination applies. Article 10 guarantees that prisoners are treated humanely, even if they have committed a crime. This principle is further emphasized in General Comment No. 21, adopted at the forty-fourth session of the Human Rights Committee, which requests detailed information on the functioning of the prison system in each State party. Importantly, it emphasizes that no penitentiary system should be exclusively punitive in nature, but should instead aim primarily at the rehabilitation and social rehabilitation of the prisoner.[81]

- Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union: The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union stipulates that all public policies in EU Member States should be guided by a human rights framework. Article 1 (dignity) and Article 21 (non-discrimination) contain provisions to reinforce the principle of fair treatment and equality for prisoners in prisons and to prevent discrimination against prisoners on the basis of their type of offense. However, although this Charter is not directly binding on Türkiye as a non-EU member state, given Türkiye’s EU accession process and its desire to become a party to the EU, it should be taken into account in preventing unfair treatment of Political prisoners in Türkiye within the framework of the EU accession process and harmonization laws.

- United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for Non-custodial Measures (Tokyo Rules): The Tokyo Rules underline the principle of non-discrimination and emphasize that non-custodial measures should be applied consistently regardless of a person’s political opinion or belief (Rule 2.2). The flexible nature of these measures, tailored to the nature of the offense and the offender’s background, should be extended to political prisoners.[82]

- Council of Europe Prison Standards: The Council of Europe provides a comprehensive framework for prison conditions, requiring all member states to comply with certain human rights standards. It provides for decent conditions for all persons in prison, guarantees equal rights for political prisoners as for other prisoners, and prohibits discrimination. It emphasizes the need for fair and humane treatment of detainees and prisoners.[83]

- European Commission Türkiye Reports: In the 2023 Türkiye report, evaluations on the penal execution system and probation practices, overcrowding in prisons due to the volatile political dynamics in recent years, deficiencies in probation and parole practices and the effects of this situation on the rehabilitation of prisoners were discussed. It was also emphasized that prisoners’ rights should be respected and rehabilitation processes should be improved.[84] Likewise, in the 2024 Türkiye report, findings on the judiciary and fundamental rights were made, differential treatment of political prisoners and detainees was mentioned in relation to the execution regime, the isolation of detainees and prisoners increased as collective activities are still limited and arbitrary, there is a tendency for Administrative and Observation Boards to arbitrarily delay the parole of prisoners, and the probation system needs to be improved.[85]

- Recommendations of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe: In its recommendations covering the management of penal institutions, staff training, rehabilitation of prisoners and improvement of probation practices, the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe stated that the aim is to bring the penal system in Türkiye up to the international standards set out in Recommendation (2006)2 of the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe to Member States on the European Prison Rules.[86]

- Relevant Recommendations of the Council of Europe: Within the framework of the Council of Europe, two important sets of recommendations and provisions stand out as important references for the evaluation of probation and early release mechanisms in Türkiye, especially for political prisoners.